If asked, many early years and special school teachers would probably say that one of the first things children should learn is to recognise, and later write, their name. One single word, yet many children seem to find this difficult and it can take a surprisingly long time to achieve.

The main reason for this difficulty is down to timing. The child is at the beginning of reading instruction, but many names require knowledge of the Alphabetic Code that is usually taught later in a phonics programme. If your name is Dan, Mim or Meg, you’re at an advantage in the name game. Your name is decodable in those early stages, so your task will be relatively easy. If you are called Jordan, Khadijah or Kayleigh, you won’t study the sounds in your name for quite a while and you won’t yet work on words of more than one syllable – but you are still expected to recall your name. It’s quite a challenge and something of a leap of faith for the child unless they are heavily supported.

Another reason names are difficult is that many of the names we are familiar with today are names from other languages. Irish names are in Gaelic which has its own set of sounds and sound spellings which (unless you are a Gaelic speaker) will not be familiar to you. I have a friend called Ciara which is pronounced ‘Keera’. To make things even more interesting (or should that be complicated) names are often anglicised. This has happened to Ciara which is also spelled Kira or Kiera. French names present a similar challenge, often ending in ‘tte’ such as Charlotte and Colette.

Names of Middle Eastern and Asian derivation are even more interesting because the symbols used in those language are completely different from those of English. This means that names are transliterated (phonetically) into English characters. It is a feature of the English Alphabetic Code that some speech sounds can be represented in more than one way, by more than one sound spelling. So, when people transliterate a name, they have a whole bunch of sound spellings to choose from… and we are a creative bunch. The result is that we can have multiple spellings for the same name. For example, the hugely popular name مُحَمَّد is written as Muhammed, Muhammad, Mohammed, Mohamed, Mohamad and in other ways.

And there’s more… some languages have sounds that don’t appear in English. The name Ahmed should be pronounced A /ckh/ med rather than /Ar/ med. The /ckh/ sound is not in an English speaker’s speech repertoire and many people struggle to say this sound accurately when they learn Arabic or Hebrew.

Historically, there has been copious amounts of angst associated with choosing baby names. The result was generations of people being called by a relatively small set of fashionable but conventional names. I worked at a school where there were so many Julies (all of a similar age) that we added words or numbers to indicate which Julie we meant. As well as office Julie and nurse Julie, I had ma’Julie who was the Julie I worked closely with on my team.

When I had my youngest child, I wanted to call him Caleb, but my husband insisted it was far too ‘different’ and would result in him being taunted in the playground from day one with catastrophic psychological consequences. We called him Tom. Twenty-six years later he is psychologically fine, but I think this would also have been the case if I had called him Caleb. All these years later, I am pleased to say the very opposite is true. People love being creative when naming their beloved offspring. They not only want to choose unusual names, but they also strive to make them unique. The result is they invent new ways to spell names. Here are a few examples from my travels around schools: Tomi, Daiton, Lillie and Marlee.

All this goes a stage further though when, in a search to represent sounds in names, new sound spellings are ‘invented’ by people. Here’s an example of a name I saw recently, Aayshan (pronounced /Ai/shan). The sound /ai/ is not represented by a sound spelling aay in any English words. Well actually it is… now… because someone just created it. That’s the point – that’s just how English has changed over time, and we have to roll with it. As Stephen Fry says, ‘it is important to keep remembering that language is – and should be – evolving’.

Names can be tricky. So how do we help our youngsters win the name game?

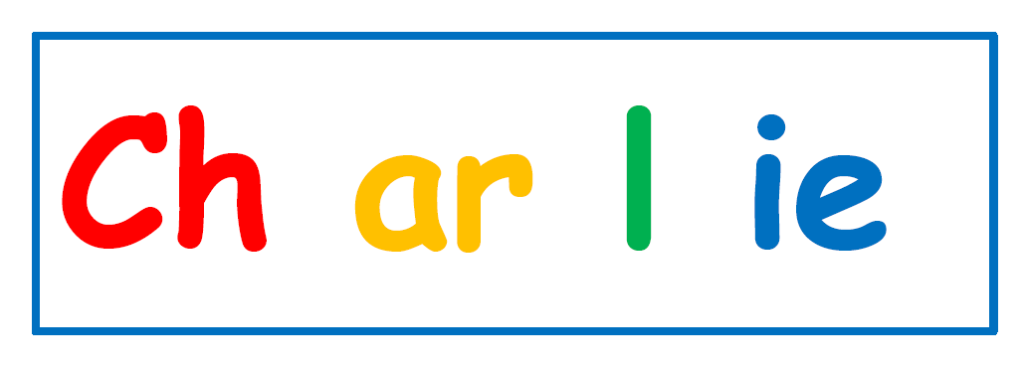

We may need to think very carefully about how to interpret the written version for children. Coding the names, so that it is easy to notice the sound spellings and their relationship to the spoken sounds, really helps, as long as it is accompanied by the child being shown (several times) how the sounds in their name match to the sound spellings.

Here’s my own name (typical of my age) coded: A nn. I have separated the sound spellings and I have highlighted one of them in bold because it is made up of two letters; it is now clear that those letters are functioning together as a single unit and represent one sound. With a simple explanation and some modelling of blending and reading, the relationship between the sounds in my name /a/ /n/ and the sound spellings A nn are clear.

Coding names like this lends itself to word-building, not with single letters but with sound spellings. Let’s look at the name Jack. Instead of giving the child four letters to put together to construct their name, let’s code it and focus on segmenting the word and matching sound spellings to spell the word in sequence.

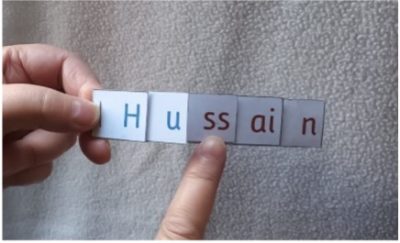

A rather fun way of working on names is my own creation, the Flippie. The name is coded and written on cards that are stacked and stapled together. When the child runs their finger across the cards, the sound spellings ‘flip up’. Doing this and saying the name at the same time, so that there is correspondence between the sound the child is saying and the sound spelling that flips up, is a great way of reinforcing the structure of the word.

The key thing with names is that information about any aspect of the code that is ‘advanced’ for that pupil should be accompanied by frequent, appropriate, simple explanations of the inconvenient bits of code and/or the complexity of word structure. It’s not something that happens once and is taken as job done.

Being told something that is ‘advanced’ in comparison to what they are being taught in phonics lessons can be destabilising for some children. So, it’s also helpful to reassure them why we are doing this. We have to tell them this now, but they are not to worry, we will be working on this in class soon. My mantra is, ‘we haven’t done this yet, but we will do’.

So, looking back to our initial question, ‘What’s in a name?’, it seems the answer is, ‘Quite a lot’!

* * *

Ann Sullivan has over 30 years’ experience in mainstream and specialist education. Based in the UK, her career includes roles as a KS1 and KS2 class teacher, SEND literacy teacher, school-based Special Educational Needs Coordinator (SENCO), an advisory teacher for pupils with special educational needs and a Specialist Leader in Education (SLE). She is on the writing team for pdnet (a network for those supporting children with physical disabilities in schools) and is a trustee of Speaking Out Forum (a charity that gives young people with SEND the chance to ‘have a voice’). Ann is now a literacy consultant, trainer and writer and creator of the Phonics for SEN programme.